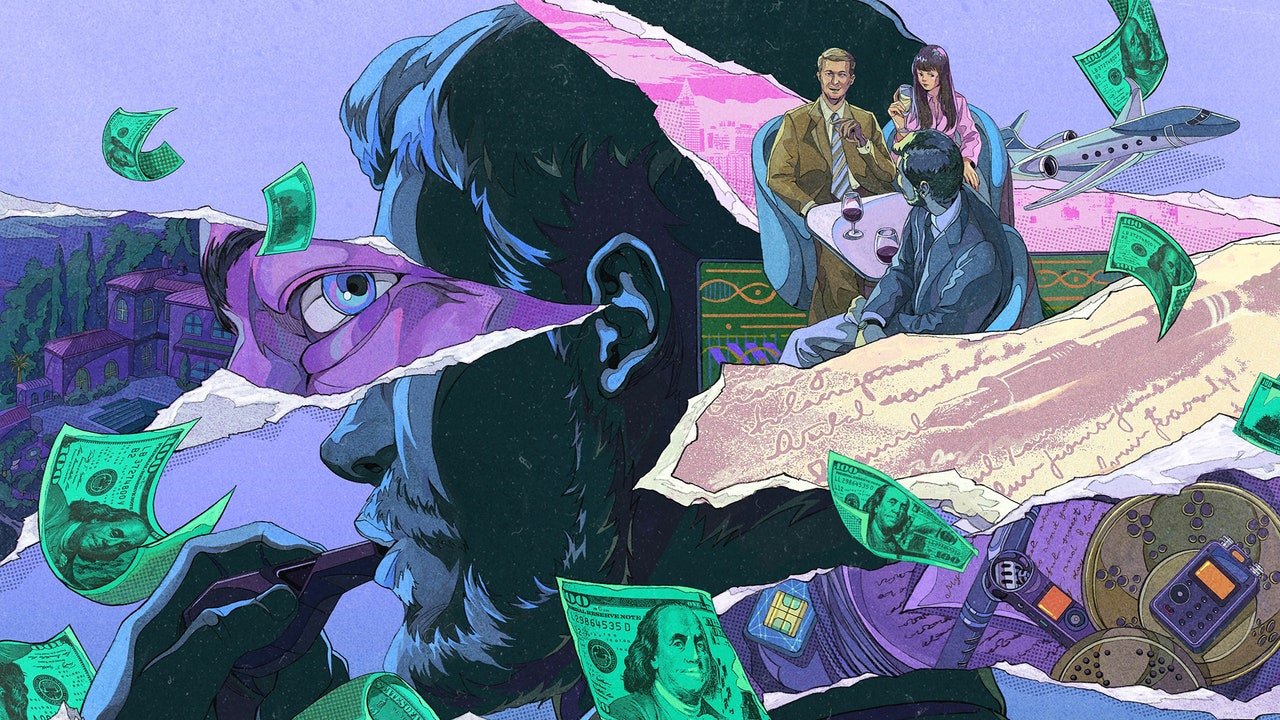

In the first meeting, King would regale Overum with stories about his experience as a developer and describe a variety of investment opportunities that Overum thought seemed too good to be true. Time and time again, he seemed to tell Overum that if these projects went as planned, he could expect a nice return on his investment, all with seemingly little risk.

One opportunity stuck out to Overum: land that King was preparing to develop. For the project, he had told Overum, he would have to raise millions of dollars in just a short period of time. The amount of money and the urgency of the timeline seemed strange to Overum. “Someone with that much experience, someone who has done all the things he’s claimed to do, shouldn’t need an investor to make sure a project gets off the ground,” Overum told me. Something strange was going on here, Overum was pretty sure.

It would be important for Overum to continue to develop the relationship and determine what additional information he could extract by posing as a potential investor. King suggested they meet again, this time at a luxury hotel, for some fun followed by business.

When Overum agreed to let me shadow him that night, I watched him deftly channel his character and stay alert for any speed bumps that might have spoiled the plot. The advent of high-definition cameras on mobile phones, for example, is a major danger for undercover work. I noted that Overum ducked away at several points to avoid ending up in the background of someone’s photo.

To do this work well requires internalizing this paranoid hypervigilance while still projecting a graceful confidence. Dealing with these contradictions, I quickly learned, is not easy. When someone asked that night at the hotel how Overum and I knew each other—a question I had even prepared to answer—I froze. Should I blow Overum’s cover on a simple introduction? Expertly and casually, Overum jumped in, describing us as old friends, turning the conversation into safe territory.

To see Overum in the hotel’s foyer with white marble floors was to see someone uncommonly balanced and clearly in his element. In the background I could hear him talking about his supposed industry with a level of expertise usually reserved for true industry veterans. At once he was completely in character – but also, apparently, completely himself.

Later that evening, after leaving King, I asked Overum if anything King had told him might be incriminating. Overum told me that his claims will only prove interesting when he keeps digging and determining whether or not they are true. “If he lied to us about something, then yes,” Overum said. “You can’t misrepresent your wealth or assets to potential investors. That’s fraud.”

It was more than just the financially enticing quirk of the federal whistleblower law that drew Overum toward this line of work. His own family had been shaken by fraud, he says. While Overum was still quite young, he explains, his father made a ruinous investment. The details were always unclear, but the event cast a long and deep shadow. “It was a scam,” Overum says succinctly. “My father lost everything.” He suffered, too: His family moved around a lot in the wake of the incident, and Overum says he turned to alcohol and drugs as a teenager.

In the 20s, Overum started working in sales. “I learned to read and respond to people’s body language,” he says. “I learned people’s stories and how to take advantage of them.”